Last weekend, with Covid-19 containment measures kicking in again across Europe, my old friend Marcel and I managed to sneak away for a classic (and fully legal!) Dead Emperors’ Society road trip. The original plan was to visit Cologne for its famous 12 Romanesque churches, but Germany imposed quarantine on people from our part of Holland so that didn’t work out.

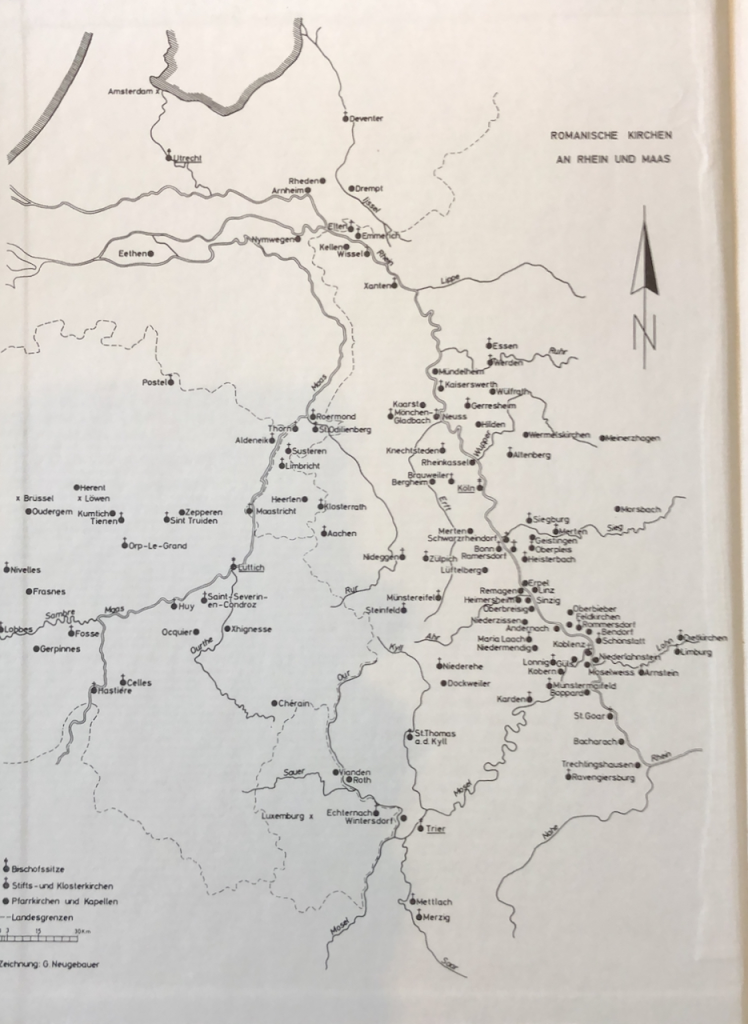

Fortunately a few years ago I bought a used copy of Kubach & Verbeek’s Romanische Kirchen an Rhein und Maas. It is old but it is still the authority on anything Romanesque in the Rhine and Meuse valleys. Cross-checking with travel restrictions and church concentrations, we ended up in Luxembourg.

After some wine-tasting (mandatory on our trips, this time we sampled Luxembourg Crémant and Pinot Noir) we ended up in the small town of Echternach, perched on the river Sauer which today forms the border with Germany. Echternach abbey was founded in 698 by Saint Willibrord, a monk from Yorkshire who was responsible for Christianizing much of what today is The Netherlands.

The feeling of standing face to face with ancient objects and buildings, especially if they’re over 1000 years old, for me almost goes beyond description – a magical historical sensation probably comes closest. This is what I enjoy so much about our trips – coupling academic art historical knowledge with experiencing buildings and objects firsthand.

On our first trip, many years ago, we saw the c. 800 AD ‘Westwerk’ of the Abbey at Corvey in Central Germany, and Bishop Bernward’s bronze church doors at Hildesheim. Standing so close to works of art that have survived a full millennium made me go very quiet – and also makes me want to return time and again.

These medieval buildings and objects, and their histories, appear to be much better known and loved in Germany than they are in the Netherlands. We can blame the romanticism of 19th century nationalists: when they looked for an ideal historical example for Bismarck’s united Reich, they ended up with the Ottonian to Hohenstaufen periods, c. 1000-1300, as Germany’s Golden Age. Like much 19th century nationalist mythology, it has stuck until today.

In contrast to Echternach’s restored church, the 8th century crypt is original and this is where I experienced my strongest ‘historical sensation’. We were surprised to find that Kubach/Verbeek did not cover it – until the penny dropped: this Carolingian crypt is simply too old to be considered Romanesque.

One of the naves holds a staircase that descends to the ‘Willibrord fount’, where spring water comes bubbling up – a reference to St. Willibrord’s baptisms.

The abbey’s most prized relics, Saint Willibrord’s bones, sit in a sarcophagus that is also Merovingian, right below the altar of the church upstairs. You can just see it in the picture – it is hidden inside an elaborate neo-gothic baldachin in white Carrara marble, created by Genovan artist Guiseppe Novi in 1906. You can also see the hole in the roof of the crypt that leads directly to the altar above – establishing a direct spatial link between the priest celebrating mass upstairs and the relics of the Saint down below.

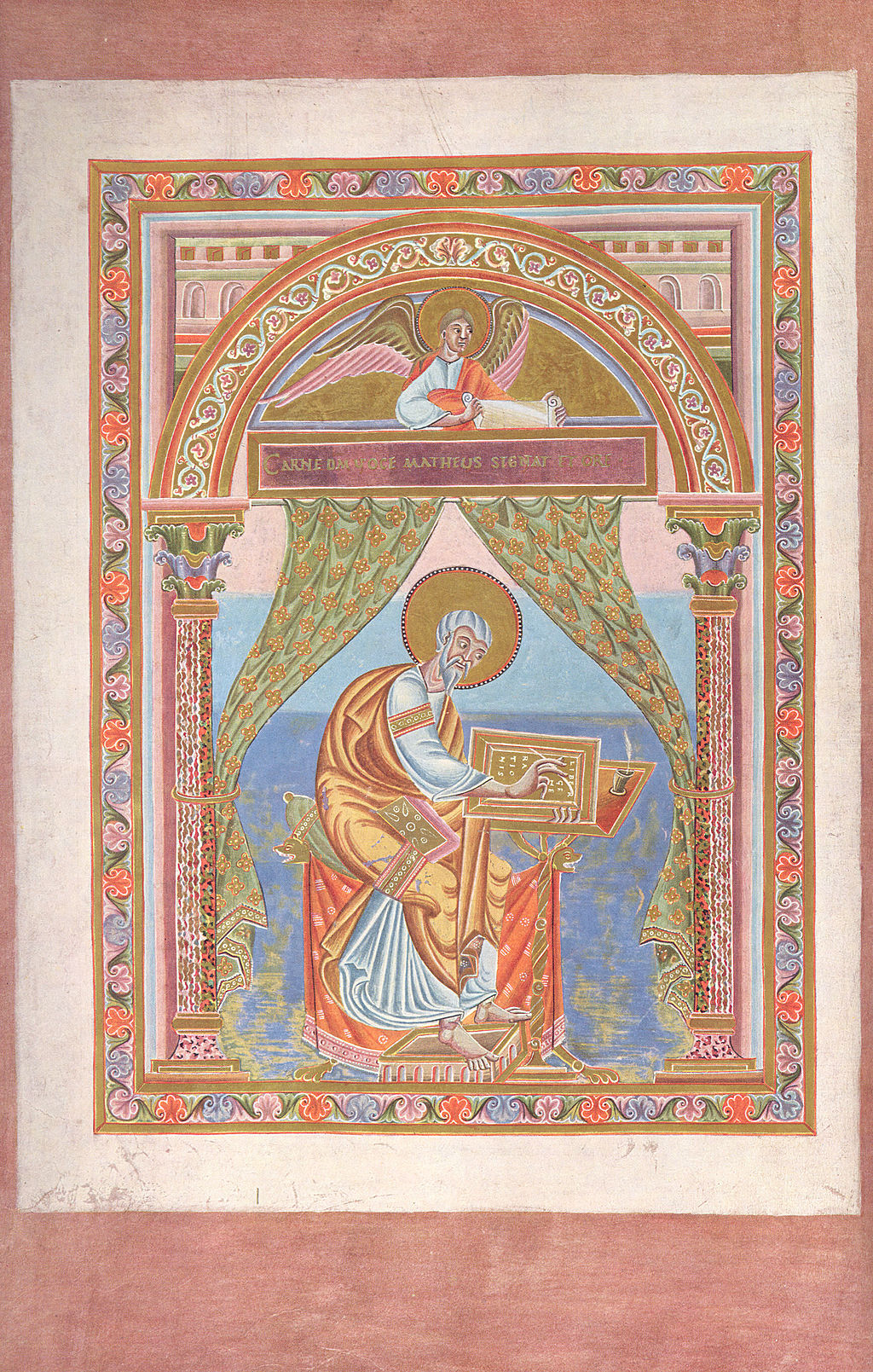

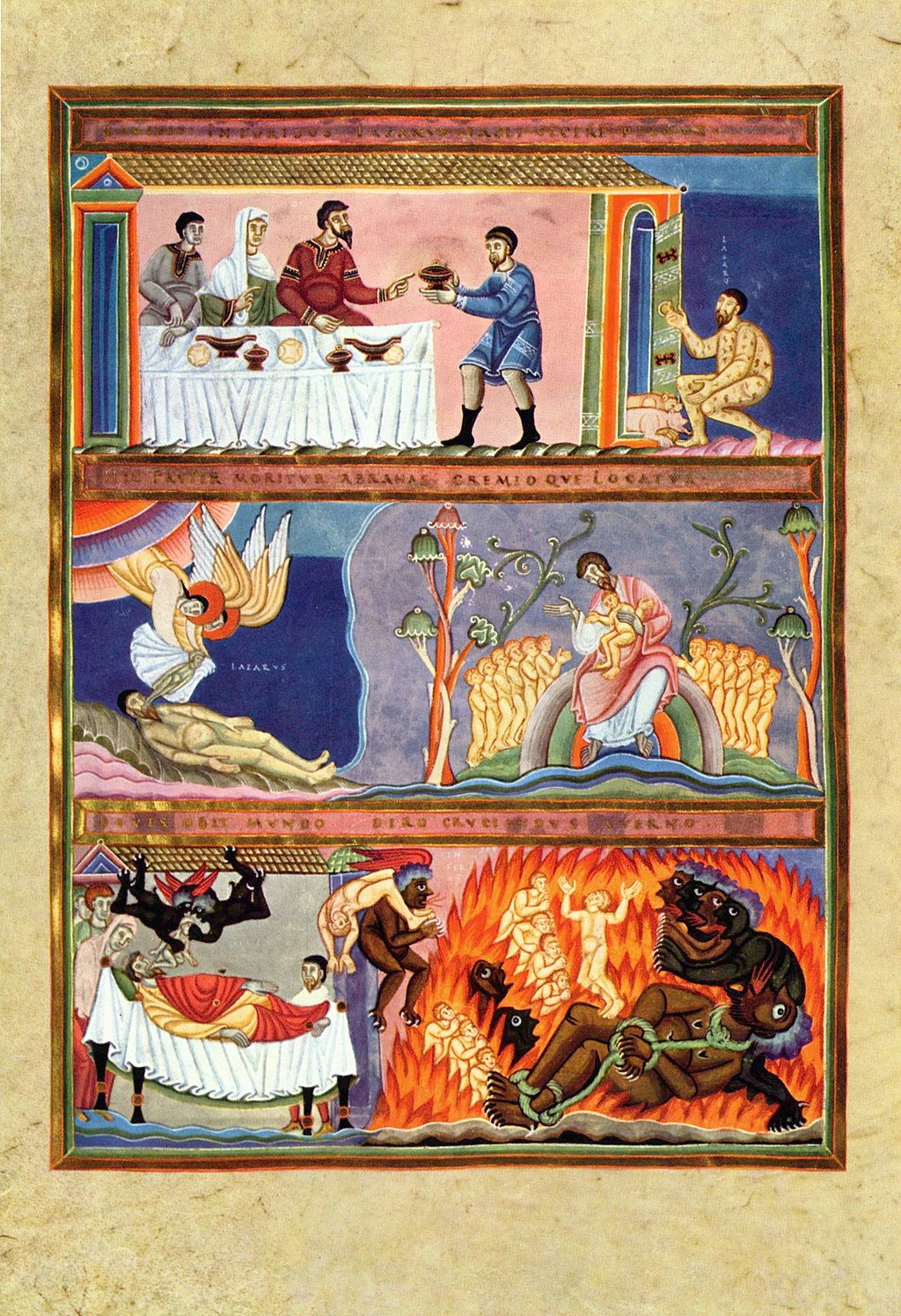

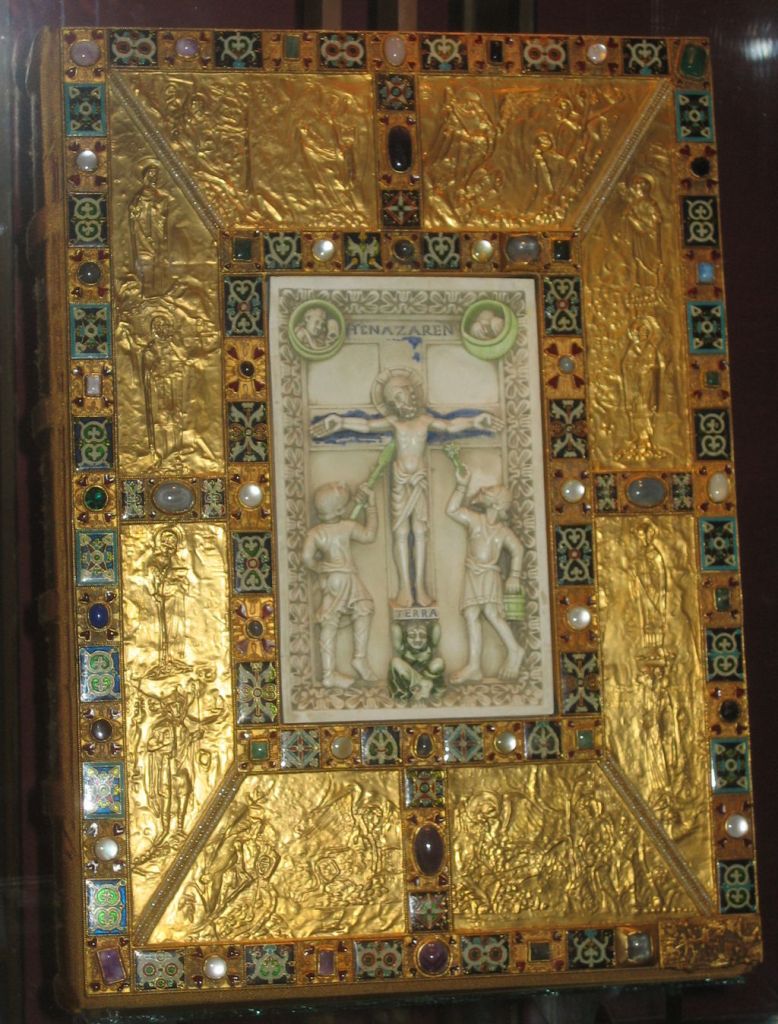

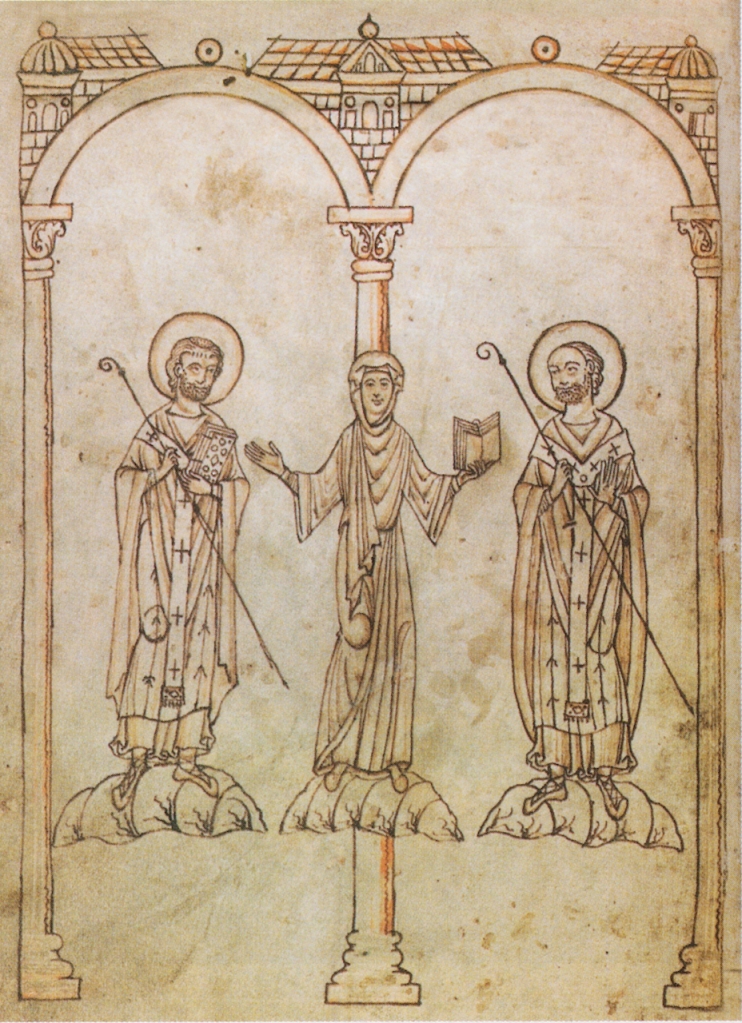

Abbeys from the era of the Carolingian Renaissance, like Echternach, contained important scriptoria, workshops where books were copied and illuminated with magnificent miniatures. Echternach is famous for creating many Gospel Books. These evangeliaria contained the four gospels of the New Testament. The most famous is the Codex Aureus Epternaciensis or Golden Codex of Echternach from c. 1040, kept at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum at Neuremburg. It is unfortunate for the abbey museum that none of the books created at Echternach have remained in its collection: all they have are images and facsimiles. The originals of these precious books have ended up in libraries across Europe – not so surprising, as they were often commissioned from the Abbey by imperial princes for use as gifts.

In case of the Codex Aureus its history is unclear: the book’s front cover, with its ivory centrepiece, is some 50 years older than the manuscript and was probably commissioned by Emperor Otto III and Empress Theophanu, but the manuscript was completed after their deaths, and scholars do not agree on the book’s original beneficiary.

Moving to the Romanesque nave of the (reconstructed) abbey, there are alternating columns, with modified corinthian columns in the middle of each blind arch, and square pillars, some in alternating layers of natural stone, linking the arches. This feature created the link with another treasure listed in Kubach/Verbeek and our next destination: the former abbey church of St. Amelberga at Susteren, in the Limburg province of the Netherlands.

This wonderful but not very well known abbey was founded in Merovingian times and had Willibrord, who later moved to Echternach, as one of its abbots. Willibrord used it as a welcome stop on his frequent travels from Utrecht, the seat of his archbishopric, to the abbey at Echternach. Two later bishops of Utrecht, Gregorius and Albericus, were buried here at their deaths in 755 and 784.

After its destruction by Viking invaders, King Swentibold of Lorraine restored the abbey and gave it to Amelberga who became the first abbess and educated Swentibold’s daughters there. The current building dates to c. 1060, and the abbey remained a Damenstift until Napoleonic times. In the 19th century, it turned into a parish church.

The crypt at Susteren is a special and unusual feature. It is above ground and protrudes beyond the apsis of the church.

A crypt of this type is very uncommon – its only prominent counterpart is in the abbey of Werden, near Essen:

This crypt is Romanesque, in contrast to Echternach’s, but it also contains a Merovingian sarcophagus. The story of how we got into the crypt – and the church’s treasury – is typical of the joys of seeking out lesser known architectural gems like these:

The church’s front door was unlocked when we arrived around 5 pm on a Sunday, allowing us to enter the vestibule. The church interior was visible, but only through a glass wall. So we walked around the exterior, took photos, and then the caretaker arrived to close the front door for the night. When hearing that we were art historians, she graciously took the time to turn on the lights and give us a complete tour of the church. Then, when she was about to close up, the church’s official guide, Mr. Wil Schulpe, passed by on his evening walk and was also happy to take us into the church’s vault and show us all its treasures.

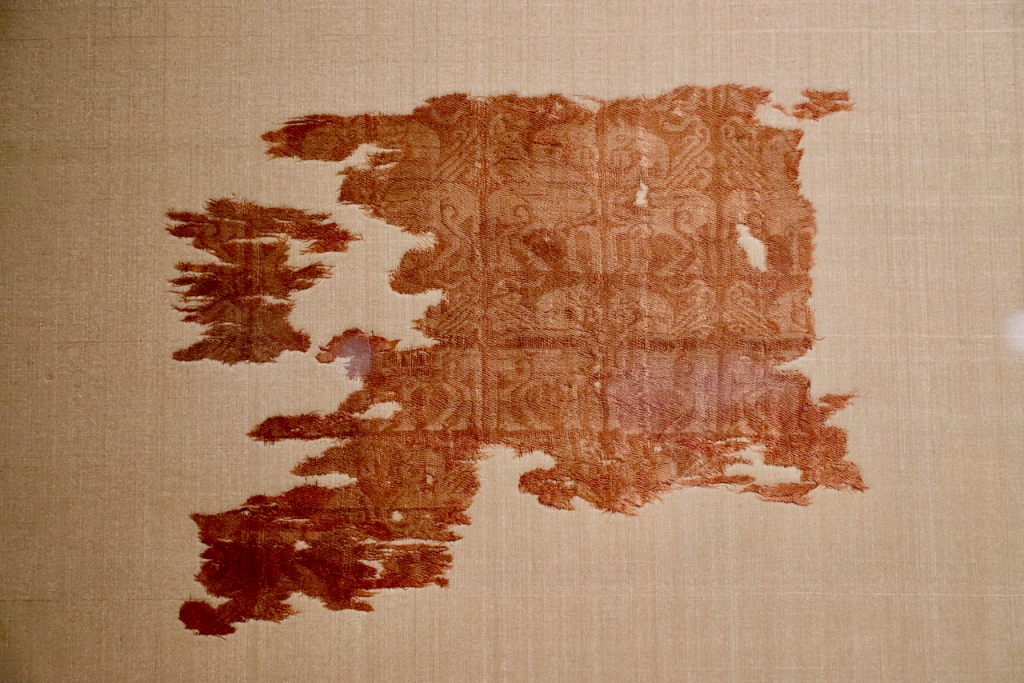

The church’s treasure also contains a famous illuminated manuscript, now being restored at Liège: the Susteren Gospel Book (Evangeliarium van Susteren).

In contrast to several gospel books named after Echternach, in this case the book wasn’t created at Susteren – it would not be realistic to expect the Stiftsdamen, daughters from royal and noble families to spend their days painstakingly copying texts like ordinary monks – but it is named after the abbey because it now resides there.

Finding these incredible treasures in a church vault that is normally closed to the public, a church that is also (unlike Echternach) completely off the beaten tourist track was a wonderful conclusion to this weekend trip.

All photos: (c) Robin Oomkes.